FRANCE’S RECOGNITION OF PALESTINE- A MEASURED STEP IN A PROTRACTED CONFLICT

French President Emmanuel Macron's announcement to recognize Palestine as a sovereign state at the United Nations General Assembly in September 2025 represents a notable development in European diplomacy toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This decision, made against the backdrop of ongoing humanitarian challenges in Gaza and stalled ceasefire efforts, aligns France with over 140 countries that already acknowledge Palestinian statehood. As a permanent member of the UN Security Council and a key player in Europe, France's move carries weight, though it also highlights the limitations of unilateral actions in resolving deep-seated disputes. It comes at a time when global frustration with the Gaza situation has intensified, following events like the October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks and Israel's subsequent military response.

This step by France, while significant, is not without precedent or controversy. It reflects a shift from initial support for Israel's self-defense to growing criticism of the war's impact on civilians, including aid restrictions and casualties. Domestically, with Europe's largest Jewish and Muslim populations, the decision could exacerbate internal tensions, as Middle Eastern conflicts have historically spilled over into French society. Internationally, it may encourage other nations to reconsider their positions, but it also risks straining relations with Israel and allies like the United States.

An Unbiased View

Implications of the Recognition

From an impartial standpoint, France's recognition serves as a diplomatic signal rather than a transformative force on its own. It underscores a commitment to international law and humanitarian principles, potentially adding pressure on Israel to engage in negotiations. However, it does not fundamentally alter the on-ground realities, such as Israel's occupation of territories captured in 1967 or the governance challenges within Palestinian areas. Israel has viewed such recognitions as potentially rewarding militancy, particularly after the October 7 attacks, while Palestinian leaders see them as affirmations of their right to self-determination.

The move could contribute to a broader momentum for dialogue, especially through upcoming UN discussions on a two-state solution. Yet, it also exposes divisions within the West: while some European countries have followed similar paths, major powers like the U.S. and Germany remain cautious, linking statehood to negotiated outcomes. In the global order, this positions France as an independent actor, challenging U.S.-led approaches and aligning more closely with the Global South's perspectives on the conflict. Ultimately, its impact depends on whether it leads to concrete actions, such as improved aid access or renewed talks, rather than remaining symbolic.

Assessing the Two-State Solution

A Historical Perspective

A two-state solution, envisioning an independent Israel and Palestine living side by side, remains a widely discussed framework for peace, though its feasibility has been debated for decades. At its core, this approach seeks to address the aspirations of both peoples: security and sovereignty for Israelis, and self-governance for Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem. A true assessment reveals both its potential merits and persistent obstacles, grounded in historical context.

The roots of this idea trace back to the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which proposed dividing the British Mandate of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. This plan, accepted by Jewish leaders but rejected by Arab states, led to the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and Israel's establishment, alongside the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians in what is known as the Nakba. The 1967 Six-Day War further complicated matters, with Israel capturing the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem, territories Palestinians claim for their state. Over time, Israeli settlements in the West Bank, now housing over 500,000 settlers, have fragmented these areas, making territorial contiguity a major hurdle.

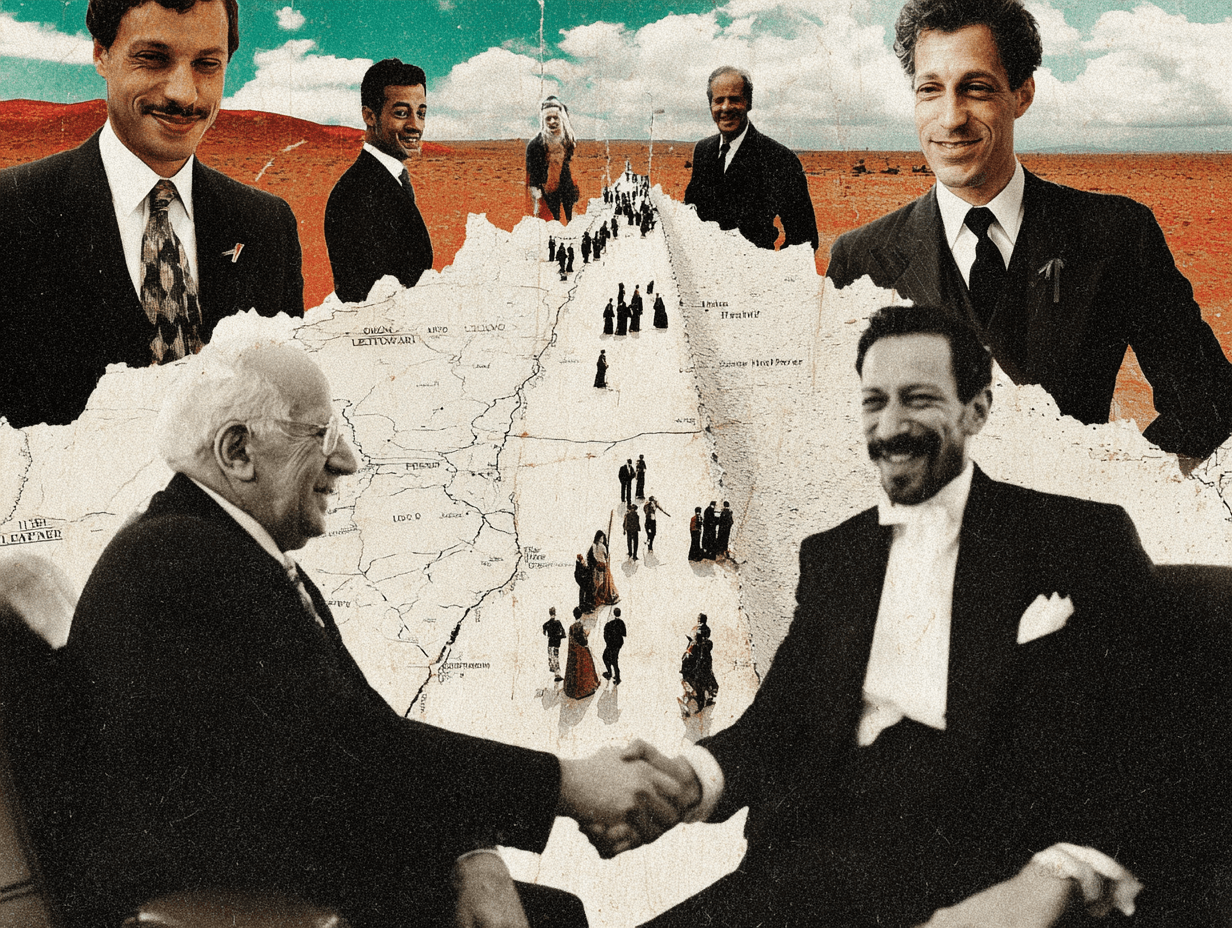

Historically, efforts such as the 1993 Oslo Accords aimed to build toward two states through interim agreements, thereby fostering limited Palestinian autonomy. These accords, signed by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat, emphasized mutual recognition and negotiation. However, their failure, due to factors including settlement expansion, violence, and leadership changes, highlights why a two-state model requires sustained commitment. The 2000 Camp David Summit and 2008 Annapolis Conference similarly stalled, often over issues like borders, refugees, and Jerusalem's status.

Why should mutual recognition and a two-state framework occur? From a balanced view, it offers a pragmatic path to end cycles of violence by fulfilling core needs: Israel's desire for secure borders and defense against threats like those from Hamas, and Palestinians' pursuit of dignity and statehood free from occupation. Historical analogies, such as the 1998 Good Friday Agreement in Northern Ireland, demonstrate that partitioned conflicts can find resolution through compromise, power-sharing, and international guarantees. In that case, addressing territorial disputes and minority rights led to relative stability, suggesting a similar model could work if adapted to the Middle East.

Oliver N.E. Kellman, Jr., J.D. Managing Partner & Executive Managing Director

“Recognition alone does not create peace—but it can spark the dialogue that finally makes it possible.”— Oliver N.E. Kellman, Jr., J.D.

Follow me

ABOUT

Created with © systeme.io