A NEW AMERICAN WEALTH ARCHITECTURE DLG PARTNERS STRATEGIC BRIEFING TO CLIENTS AND PARTNERS

Donald Trump’s initiative to create a United States sovereign wealth fund is one of the most consequential experiments in American economic strategy in decades. For the first time, the federal government is moving to formalize what other nations have honed into an art form: a national investment engine designed to convert state assets, fiscal flows, and strategic advantages into enduring wealth, resilience, and influence.

This is not yet a finished institution. It is an architecture under active construction. The legal shell is still being defined, but the behavior is already visible. The United States is beginning to act the way Norway did when it first harnessed its oil revenues, as Singapore did when it professionalized its state holdings, and as the Gulf states did when they turned hydrocarbons into global capital. The rules are not settled, the structures are still fluid, and the relationships that will define access are being formed now. That is precisely why this moment is so important.

DLG Partners issues this briefing to explain what is being built, how it is already operating in practice, where its money comes from, which companies and sectors are receiving that capital, and how sophisticated partners can position themselves as limited partners, co-investors, or even designated co-managers within this emerging system. The goal is not simply to describe the landscape but to help clients move through it with clarity, creativity, and control.

THE EXECUTIVE ORDER: BLUEPRINT STAGE, NOT FORTRESS STAGE

In February 2025, President Trump signed an executive order titled A Plan for Establishing a United States Sovereign Wealth Fund. The order did not instantly create a monolithic fund with its own board, statute, and consolidated balance sheet. Instead, it instructed the Secretaries of the Treasury and Commerce, in coordination with the Office of Management and Budget and senior economic officials, to deliver a comprehensive plan for such a fund within a defined timeframe.

That plan was tasked with answering several foundational questions. How should the fund be capitalized? What mandate should it have? How independent should it be from day-to-day politics? How should its governance be structured? How should it sit alongside existing federal programs and agencies that already deploy capital? The text of the order makes clear that the ambition is to create a vehicle capable of stewarding national wealth across generations, while reinforcing U.S. economic and strategic leadership.

In other words, the United States is at its founding moment. Norway once had to decide what to do with oil surpluses. Singapore had to work out how to manage a web of state-owned assets. Today, Washington is confronting its own version of that question: how to harness a vast but scattered asset base, a deep financial system, and a complex political order to serve long-term national interests instead of short-term fiscal needs.

Legally, the executive order launched a process rather than an institution. A true sovereign wealth fund, with permanent capital and a long-term mandate, will almost certainly require Congress to enact a charter that defines its legal personality, its powers, and its relationship to the federal budget. Until that happens, the administration has done the next best thing: it has begun using existing tools to behave like a sovereign investor, while preparing the ground for a formal fund.

HOW IT IS OPERATING TODAY: A DE FACTO SOVEREIGN ARCHITECTURE

On paper, there is not yet a single entity called the United States Sovereign Wealth Fund with a published portfolio and a public board. In practice, however, the United States is already deploying capital in a way that looks very much like sovereign wealth investing. It is using established statutes and agencies to build a portfolio of strategic stakes in critical sectors, and it is doing so at scale.

The core pillars of this de facto architecture are threefold.

First, the Defense Production Act. Title III of the Defense Production Act allows the president to allocate funds to support domestic production capabilities deemed essential to national security. Traditionally, this has meant grants, loans, guarantees, and contracts. Under the current approach, it has been interpreted more aggressively as an authority that can support direct equity and quasi-equity participation in companies. Instead of merely subsidizing, the government is taking actual stakes.

Second, specialized appropriations under new legislation, most notably the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and related defense and industrial measures. This legislation provides roughly 150 billion dollars for targeted national security and industrial base investments. Embedded within that total are dedicated pools of capital for the Department of Defense’s Office of Strategic Capital, the Industrial Base Fund, the Defense Innovation Unit, and other bodies. These pools are structured not as generic spending lines, but as investment capital designed to support specific projects and companies and to be leveraged into larger sums.

Third, the balance sheet and authorities of agencies such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the Office of Strategic Capital. The Development Finance Corporation, historically oriented toward overseas projects, has been delegated Defense Production Act authority to issue direct loans and guarantees for domestic critical mineral production. The Office of Strategic Capital has been given a substantial credit subsidy that it can leverage many times over into loans for high-priority technologies.

Taken together, these tools allow the United States to act like a sovereign wealth fund even before a dedicated legal entity is born. The capital is real, the transactions are real, and the companies receiving that capital can be named.

Given that there is no standalone sovereign wealth statute yet, it is important to be precise about where the current money actually comes from.

Part of it comes from Defense Production Act appropriations. Congress funds the DPA’s Title III account, and the administration uses those dollars to make equity investments, loans, and guarantees in firms deemed essential to national security. When the government buys a stake in a chipmaker or critical minerals producer under this authority, it is effectively deploying sovereign capital funded by those appropriations.

Another part comes from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act and similar measures. Under that legislation, the Industrial Base Fund has received 8.2 billion dollars, with 5 billion dollars explicitly earmarked for critical mineral supply chain investments. The National Defense Stockpile Transaction Fund has received an additional 2 billion dollars to build and manage stockpiles of strategic materials. The Office of Strategic Capital has received 500 million dollars in credit subsidy, which can be levered into up to 100 billion dollars in loans under federal credit rules. The Defense Innovation Unit has been allocated 2 billion dollars for scaled technology projects and nearly 100 million dollars for its own operations. All of this is appropriated money, structured for investment.

A further tranche comes from agency balance sheets under new or expanded authorities. The International Development Finance Corporation, for example, has been given responsibility for a domestic mineral production fund, 25 billion dollars in loan and guarantee capacity focused specifically on mining and processing projects in the United States. That capacity derives from the DFC’s existing capital base and its delegated authority under the Defense Production Act and other statutes.

There are also conceptual or prospective funding sources that policymakers are exploring. Tariff revenues generate tens of billions of dollars annually. There have been public discussions about directing a portion of these revenues into a sovereign fund, effectively turning border taxes into national equity. Similarly, some have proposed revaluing the Treasury’s gold holdings on the federal balance sheet, which are currently carried at a statutory book value far below market prices, and using part of that revaluation as seed capital. These ideas would require further legislative action, but they illustrate the mindset: monetizing underused public assets and cash flows into long-term capital.

COMPANIES AND PROJECTS ALREADY RECEIVING SOVEREIGN-STYLE CAPITAL

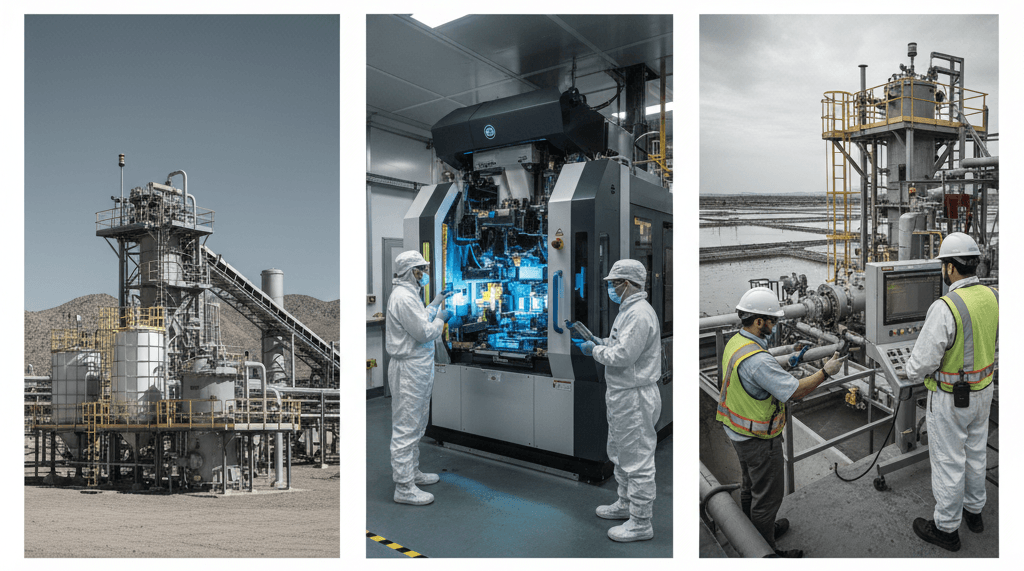

This architecture is not notional. It is already visible in concrete investments and commitments.

In the rare earths sector, MP Materials stands as a prime example. As the only significant rare earth producer in the United States, it occupies a central place in the supply chain for magnets used in everything from fighter jets to electric vehicles. Under the Defense Production Act, the Department of Defense has committed 400 million dollars in equity financing to MP Materials. This investment is structured to give the government up to a 15 percent stake in the company and is tied to long-term offtake arrangements under which the government agrees to purchase 100 percent of the magnets produced at a new facility. The investment has not only secured strategic domestic capacity; it has catalyzed an additional 1 billion dollars in private financing from major financial institutions to build MP Materials’ new “10X” plant.

In semiconductors, the federal government has taken a 10 percent stake in Intel, again through DPA funding, to support domestic chip manufacturing. Semiconductor fabrication is capital-intensive, slow to build, and strategically sensitive. By placing public equity directly into one of the most important firms in the sector, the United States is signaling that it is willing to act as an anchor shareholder in its own industrial base.

Lithium Americas, a key player in domestic lithium production, has also seen the government acquire a 5 percent stake. Lithium is essential for batteries and energy storage, which in turn underpin electric vehicles, grid stability, and defense systems. Here too, the government is acting not just as a regulator and procurer but as an owner.

Beyond these headline investments, the funding pools created by the Industrial Base Fund, the National Defense Stockpile Transaction Fund, and the Office of Strategic Capital are being deployed across a range of projects. The Industrial Base Fund’s 5 billion dollar critical mineral earmark supports mining, processing, and refining ventures across the value chain. The Stockpile Transaction Fund finances the purchase and management of strategic material inventories. The Office of Strategic Capital’s Domestic Manufacturing Loan Program has already received requests totaling 8.9 billion dollars, a clear sign of how quickly sovereign-style capital finds willing partners.

At a different scale, the 24.4 billion dollars allocated for the “Golden Dome” missile defense initiative demonstrates the same mindset in another domain. While it is not an equity investment in a single company, it represents a long-term, large-scale capital commitment to build an integrated air and missile defense system with ripple effects across the defense industrial base.

EARLY FOOTPRINTS: SOVEREIGN-STYLE BEHAVIOR ACROSS SECTORS

Even apart from these explicit stakes, the pattern of federal activity carries the imprint of sovereign wealth logic.

In critical minerals, equity, offtake, and stockpiling arrangements are being used together to secure supply chains for rare earths, lithium, and other materials. In semiconductors and microelectronics, government capital and guarantees are underpinning facilities that would otherwise be too risky or costly for private actors alone. In artificial intelligence and data infrastructure, proposed long-term commitments to build and operate data centers and compute hubs are being structured as partnerships between the state and major technology firms, with shared capital and defined strategic outcomes.

Internationally, the United States is positioning itself as the anchor destination for vast pools of allied capital. Japan has pledged substantial resources to support U.S. semiconductor, pharmaceutical, and critical industry projects. European actors have signaled readiness to channel hundreds of billions of dollars into U.S. energy, infrastructure, and technology investments over time. These flows already resemble a distributed sovereign consortium centered on the United States. As the formal sovereign fund takes shape, that consortium will likely be channeled through more coherent vehicles.

FUNDING VERSUS FORMALITY: HOW IT OPERATES WITHOUT A FINAL LAW

A fair question arises from all of this: if Congress has not yet enacted a single sovereign wealth fund law, how is this “fund” operating?

The answer lies in understanding that “fund” in this context is more about function than form.

The executive order ordered the design of a unified fund, and that design is now a subject of legislative and policy debate. But in parallel, the administration is using existing legal tools to carry out the essential functions of a sovereign wealth fund: investing in strategic sectors, taking equity stakes, leveraging public capital, and partnering with private and foreign investors to reshape industrial capacity.

The Defense Production Act, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the Industrial Base Fund, the National Defense Stockpile Transaction Fund, the Office of Strategic Capital, the Development Finance Corporation, and related entities form a cluster of instruments that collectively behave like a sovereign fund’s departments. They are financed through appropriations, credit subsidies, and delegated authorities. They invest through equity, loans, guarantees, and offtake contracts. Coordination occurs through interagency mechanisms, the National Security Council, and the Office of Management and Budget.

In the near term, this distributed approach gives the administration agility. It can act quickly in response to perceived vulnerabilities in supply chains or technology. Over the medium to long term, however, the pressure to consolidate these activities into a coherent, legislatively chartered fund will only grow, both for reasons of governance and for reasons of market clarity.

THE GOVERNANCE QUESTION

However, the final structure is drawn, governance will determine whether this experiment strengthens the American balance sheet or becomes a source of risk.

There is no shortage of warnings from analysts and watchdogs. Poorly designed, a U.S. sovereign wealth fund could be misused for political favoritism, deployed as a tool of pressure on firms, or used to sidestep Congress’s authority over spending. Questions have already been raised about transparency, the concentration of decision-making power, and the adequacy of oversight mechanisms.

At the same time, there is a robust body of global experience to draw upon. The most respected sovereign funds adhere to a set of common principles: clear mandates enshrined in law; independent boards with fixed terms; professional management recruited on a global basis; transparent financial reporting and audit; and meaningful legislative and public oversight. When sovereign funds are structured this way, they tend to support stability, reduce volatility, and act as responsible long-term investors.

For partners and clients, this is not an abstract debate. Capital that aligns itself with a well-governed U.S. sovereign platform can benefit from credibility, predictability, and long-term political support. Capital that aligns itself with a poorly governed vehicle risks entanglement in scandal, regulatory backlash, or policy whiplash. Institutions that engage early and insist on robust governance standards can play a real role in shaping the trajectory.

THE STRATEGIC MANDATE: WHERE CAPITAL IS LIKELY TO FLOW

The pattern of existing investments and the language of policy documents and public statements point toward a clear thematic mandate.

Critical supply chains and technological primacy sit at the center. Semiconductors, rare earths and other critical minerals, advanced materials, pharmaceuticals, biomanufacturing, defense manufacturing, AI infrastructure, cyber, quantum, and high-end manufacturing will continue to draw sovereign-style capital. These are sectors where commercial projects intersect directly with national power and where scale and risk profiles lend themselves to public anchor investment.

The architecture is also being designed as a magnet for allied capital. Rather than positioning the U.S. fund in competition with Norway, Singapore, or Gulf funds, policymakers are increasingly treating it as a partner and syndicator. Joint vehicles that combine U.S. capital, Japanese capital, European capital, and other allied capital around U.S. projects are already in discussion. The sovereign fund, once created, will likely be the hub of these networks.

There are indications that, over time, elements of the architecture may reach ordinary citizens in the form of mass-market wealth tools: specialized accounts, tax-advantaged vehicles, or worker and community participation schemes tied to sovereign-linked investments. These ideas remain at an early stage, but they reflect the political desire to connect elite capital markets and national wealth strategies to everyday economic life.

PATHWAYS TO PARTICIPATION FOR DLG PARTNERS’ CLIENTS

Within this landscape, there are three main routes for sophisticated partners to participate.

The first is as limited partners in sovereign-adjacent vehicles. These are funds or joint ventures in which U.S. sovereign capital acts as anchor and private or allied capital participates under negotiated terms. They are likely to be thematic: a fund for AI infrastructure, a vehicle for critical minerals, a platform for resilient manufacturing, and an infrastructure corridor partnership.

LP positions in such vehicles can offer diversified exposure to sovereign-aligned deal flow and insight into the direction of U.S. policy.

The second route is direct co-investment alongside sovereign initiatives. Here, institutions commit capital directly into projects where the U.S. fund or U.S. sovereign-style capital is already present. These deals tend to be large, complex, and long-dated. They are best suited to investors with the ability to underwrite idiosyncratic risk and the desire to be at the center of strategic transformations in specific sectors.

The third and most ambitious route is to become a designated fund or co-manager for specific mandates. In this model, a partner institution manages a defined pool of capital on behalf of or alongside the U.S. sovereign platform, focused on a particular region, sector, or theme. The sovereign side provides anchor capital and strategic parameters; the designated fund provides expertise, origination, execution, and risk management.

DLG PARTNERS’ ROLE

DLG Partners is designed to operate at the interface where government power and global capital meet. In the context of the emerging U.S. sovereign wealth architecture, this means four things.

First, strategic intelligence and translation. DLG tracks the evolution of the sovereign project across executive orders, agency actions, congressional debates, and allied agreements, and translates that into concrete implications for investors. Which sectors are rising in priority? Which agencies control which capital pools? Where are the early deals being done?

Second, structuring and negotiation. For clients seeking LP positions, co-investments, or co-management roles, DLG sits at the structuring table. It helps define the economic terms, the governance rights, the risk-sharing arrangements, and the exit options that make participation both attractive and defensible. This includes securing advisory roles, information rights, and protections that reflect the unique nature of sovereign-linked vehicles.

Third, project and platform design. Many sovereign-aligned opportunities begin life as ideas rather than fully formed transactions.

DLG works with clients and public partners to shape projects and vehicles so they are legible and compelling to both sides. That entails aligning legal structures, technical specifications, and narratives with sovereign priorities and market expectations.

Fourth, long-term governance and reputational stewardship. The relationship with a sovereign platform does not end at signing. DLG continues to help clients manage evolving oversight, navigate political shifts, maintain transparency, and respond proactively to public scrutiny.

REPUTATION AND OVERSIGHT

Engaging with a U.S. sovereign wealth architecture means entering a space that is as political as it is financial. The very idea of a national sovereign fund has mobilized both champions and critics. Supporters see a chance to build a long-term wealth engine, reduce vulnerability, and secure critical capacities. Critics see potential for abuse, favoritism, and diminished checks and balances.

In this context, how an institution behaves matters as much as where it invests. Clear impact, robust governance, transparent reporting, and readiness to answer hard questions are no longer optional. DLG works with clients to integrate these elements into their sovereign-linked strategies from the outset, so that they are positioned not merely as beneficiaries of public capital but as responsible co-stewards of public purpose.

SEIZING THE MOMENT

The United States is in the midst of a structural shift in how it thinks about wealth, power, and capital. The move toward a sovereign wealth fund is not an isolated policy idea. It is part of a broader reorientation in which the state is prepared to act as a strategic investor in its own future, and to invite allies and private partners into that project.

The legal edifice is not yet complete. The formal United States Sovereign Wealth Fund has not yet been chartered by Congress. But the behavior is already here. The government is taking stakes, providing leveraged financing, anchoring projects, orchestrating allied capital, and building supply chains with a level of intentionality that marks a new chapter.

For DLG Partners’ clients and strategic allies, this is the entry point. The stage is not crowded yet. The institutions that move now, with discipline and imagination, will not simply participate in a new funding source. They will help define how that source is structured, governed, and perceived.

As limited partners in sovereign-adjacent funds, as co-investors in landmark projects, or as designated co-managers of specific mandates, DLG’s partners can position themselves at the heart of a new American wealth architecture. The opportunity is not just to benefit from a sovereign fund, but to help write its story.

Oliver N.E. Kellman, Jr., J.D. Managing Partner & Executive Managing Director

“Nations do not rise on spending — they rise on what they choose to own.”— Oliver N.E. Kellman, Jr., J.D.

Follow me

Created with ©systeme.io